Grammar

How we talk about future situations

People learning English are often confused by the many ways in which it is possible to talk about future events. They are not helped by the fact that some writers (eg, Sinclair1) claim that the construction with will in front of the base form (bare infinitive) of the verb is the future tense, while others (eg, Quirk et al2) claim that there is no future tense in English. Learners who have read in one book (eg, Thomson and Martinet3) that the BE + going to form expresses the subject’s intention to perform a future action will wonder what intention is present in It’s going to rain. Some course books appear to claim that there is only one way of expressing the future in any given situation, but learners will meet many native speakers who claim that several ways are often possible, and that there is no difference between them. In this blog post, I hope to clear up some of the confusion. Let’s begin by making two clear points: 1. There is little point in considering that English has a future tense. It is more realistic (and helpful) to think that there are several ways in English of expressing futurity. 2. Although each of the ways expresses a different way of looking at future situations, the speaker often has completely free choice at the moment of utterance, and there can be some overlap of meaning. There is often no single—or even ‘most appropriate’—form for a given situation. Now let’s look at the five most common ways of talking about future situations. We’ll do this by considering what forms are possible for the example “Lindsay (fly) to New York next month”.

1. The present simple (non-past, unmarked) tense – Lindsay flies…

In English, as in many other languages, the so-called ‘present’ tense functions more like a default tense; it is used when there is no need for any additional temporal or aspectual information carried by other forms. The time of the situation denoted by the present simple tense of the verb can be past, present, future, or even unspecified. Let’s look at Lindsay’s future flight. If we imagine the speaker mentally seeing Lindsay’s schedule, and presenting a neutral fact without any of the overtones suggested by other ways of expressing the future (which we shall come to below), we can simply say:

Lindsay flies to London next week.

The futurity is shown by the context (for example, the previous mention of a schedule) or by explicit-markers (such as next week in the example above).

2. The present progressive (continuous) – Lindsay is flying …

A better name for this aspect might be durative, as it is used when the speaker wishes to indicate both that the situation spoken of has duration and that that duration is limited. The fact that the situation has a beginning and an end, and that these are not considered remote in time, is more important than precisely when these occur. Consider these three utterances:

1. I am writing some notes about the English language. 2. The number 22 tram is running through Florence this week. 3. I am meeting my wife at the pub this evening.

In [1], the limited duration of the writing is clearly understood from the context. In [2], the known context of the normal route of the 22 tram (which does not usually include Florence) confirms the limited duration of the situation. It is perfectly correct for this to be said at 3 a.m., when no number 22 tram is actually running. I, the speaker, can say [3] because I know that my wife and I arranged the meeting this morning. The arrangement to meet has limited duration – it began this morning and ends when we actually meet. Considered this way, it is useful to think that one of the ways of using the progressive form is to indicate an arrangement. If an arrangement of limited duration is what the speaker has in mind, then the example sentence is now realised as:

Lindsay is flying to London next week.

As with the present simple, the futurity is shown by the context or by explicit time-markers.

3. BE + going to – Lindsay is going to fly…

Forms with BE + going to possibly originated in such utterances as:

4. We are going to meet Andrea at the cinema.

These types of phrases are spoken when we were literally going, as in ‘on our way to meet Andrea’. At the moment of speaking there was present evidence of the future meeting. This use has become extended to embrace any action for which there is present evidence – things do not have to be literally moving. Consider now these two utterances:

5. Look at those black clouds. It’s going to rain. 6. Luke is going to see Bob Dylan in concert next year.

In [5] the present evidence is clear – the black clouds. In [6], the present evidence may be the tickets for the concert that the speaker has seen on Luke’s desk, or it may simply be the knowledge in the speaker’s mind that s/he has somehow acquired. This explains why, when the grammatical subject of the verb is capable of planning, there may be little practical difference between the use of the progressive form and the BE + going to form. However, with a grammatical subject incapable of planning, there is a difference:

3. I am meeting my wife at the pub this evening. 3a. I am going to meet my wife at the pub this evening.

Compared with:

5. It’s going to rain. 5a. It’s raining. 5b. *It’s raining tomorrow.

In [3], the speaker has made the arrangement with their wife. In [3a], the present evidence can be any or all of the speaker having made the arrangement, having been informed by their wife of the arrangement, or having recently made a plan. The circumstances surrounding the situations in [3] and [3a] differ, but the practical result is the same: the speaker has free choice between the two forms. Neither is ‘better’, ‘more appropriate’, or ‘more correct’. In [5], the present evidence is something like the presence of black clouds, or the speaker’s knowledge of the weather forecast. In [5a], it is impossible for an arrangement to be made for future rain, and therefore the progressive form used here cannot be referring to future arrangement. The context will therefore inform us that rain is actually falling as the utterance is made. The addition of a time-indicator cannot make the impossible possible, therefore [5b] is not a grammatical utterance. If the speaker has present evidence of next week’s flight, then the example will be realized as

Lindsay is going to fly to London next week.

4. Modal will – Lindsay will fly …

Will is a modal and, like the other modals, has two core ideas. The two core ideas for most modals are: (a) the ‘extrinsic’ meaning, referring to the degree of certainty of the event/state, and (b) the ‘intrinsic’ meaning, reflecting such concepts as: ability, necessity, obligation, necessity, permission, possibility, volition, etc. The extrinsic meaning of will is exemplified in:

7. Emma left three hours ago, so she will be in Manchester by now. 8. There will be hotels on the moon within the next 50 years. 9. The afternoon will be bright and sunny, though there may be rain in the north.

In all three examples, the speaker suggests 100% probability, i.e. absolute certainty; (may would imply possibility, must logical certainty, to take examples of two other modals). Note that while certainty in [8] and [9] is about the future, in [7] it is about the present. It is the absolute certainty, in the minds of speaker/writer and listener/reader, that can give the impression that forms using ‘the will future’ are some way of presenting ‘the future as fact’. Some writers therefore call this form ‘the Future Simple’. Weather forecasters, writers of business/scientific reports, deliverers of presentations, etc., frequently use will, and learners who encounter English more through reading native writers than hearing native speakers informally may assume that it is a ‘neutral’ or ‘formal’ future. In fact the particular native writer or speaker is simply opting to stress certainty rather than arrangement, plan or present evidence. The intrinsic meaning of will is exemplified in:

10. I’ll carry your bag for you. 11. Will you drive me to the airport, please? 12. Jed will leave his mobile switched on in meetings. It’s so annoying when it rings.

These examples show what we might loosely call volition, the willingness or determination of the subject of the modal to carry out the action. Note that [12] is not about the future, and in [10] and [11] the futurity is incidental. It is context rather than words which gives the meaning. So, our original example can clearly be realized as:

Lindsay will fly to London next week.

Without expanded context or co-text, we cannot be sure of what is implied by Lindsay will fly . If the background has been that she is scheduled to fly next month, but there is an urgent need for her to be in London soon, the speaker of this utterance is indicating Lindsay’s willingness to fly earlier than intended. In a different context, known to both speaker and listener, the speaker is indicating the certainty of Lindsay’s flight tomorrow, possibly even because of the speaker’s own volition. Outside the context of gap-fill exercises this is not a problem. Note that some writers used to insist that for this way of expressing the future, shall could (Alexander4) or ought to (Wood5) be used for first person forms. This ‘rule’ was never true except for a minority of speakers of BrE, and can safely be ignored by learners.

5. Modal will+ progressive – Lindsay will be flying

… will be … -ing can have two possible overtones, both stemming from the combination of the ideas of certainty (will) and limited duration (progressive form). The first possibility is that the speaker is describing a situation already begun, having duration, and not completed by the time mentioned or implied.This would be explicit in:

13. At 5 o’clock tomorrow Henry will be driving up the M6.

The second possibility is that the speaker is more concerned with the pure certainty of the action happening than any volitional aspect that might be implied by the use of will by itself. This idea can be illustrated more clearly in the following examples. If someone says “I’d like to know what Joan thinks about this”, responses might be:

14. I’ll see her tomorrow; I’ll ask her. 15. I’m seeing her tomorrow. I’ll ask her. 16. I’m going to see her tomorrow. I’ll ask her. 17. I’ll be seeing her tomorrow. I’ll ask her.

In all four examples, the I’ll ask her indicates the speaker’s willingness (confirmed by context). In the first half of the utterance, [14] indicates the speaker’s willingness to see her, [15] the speaker’s knowledge of an arrangement already made to see her, [16] the speaker’s awareness of present evidence of the future meeting and [17] the speaker’s simple presentation of the fact of the future meeting. It is claimed by some writers, with some justification, that the use of will be …-ing implies, by its lack of reference to intention, volition or arrangement, a ‘casual’ future, the ‘future as a matter of course’ (Leech6).. So, the realization of our standard example can be:

Lindsay will be flying to London tomorrow.

Other ways of talking about the future

We have looked at five common ways of expressing the future. We will now look very briefly at other ways. So far we have considered the five ways of referring to the future that are considered by some to be ‘tense’ forms: Present Progressive, Present Simple, BE going to, will, and will be + …-ing. There are many other ways of referring to future situations, each with its own particular shade of meaning. Some of these are considered briefly below.

BE + to

This form is not common in informal conversation. It refers to something that is to happen in the future as a plan or decree:

Lindsay is to fly to London next week.

It is common in news reports. In headlines BE is frequently omitted:

18. Obama to meet Putin.

BE + about to

This form is used to refer to planned future events that are expected to happen soon:

19. 2,300 workers at the Manchester factory are about to lose their jobs.

The soon-ness often carries the idea that the subject is very close to the point of doing something:

Lindsay is about to leave for the airport.

Other idioms with BE

There are a number of other expressions with BE which have some form of modal-type meaning (ability, obligation, etc), and which point to the future. These include: be able to, be bound to, be certain to, be due to, be likely to/that, be meant to, be obliged to, be supposed to, be sure to.

Idioms with HAVE

Expressions with HAVE, such as have (got) to and had better, have some form of modal-type meaning (necessity, obligation, etc) pointing to the future.

Lindsay had better fly to London next week.

Other modals

Apart from will, discussed earlier, other modals can also used with future reference:

- Lindsay can fly to London next week. (possibility/ability/permission)

- Lindsay could fly to London next week. (more remote possibility/ability)

- Lindsay may fly to London next week. (possibility/permission)

- Lindsay might fly to London next week. (more remote possibility/ permission)

- Lindsay must fly to London next week. (obligation)

- Lindsay should fly to London next week. (possibility/suggestion)

Expressions with would, with some form of quasi-modal meaning (preference) pointing to the future, include: would rather, would sooner, would just as soon. Verb + to- infinitive Some full verbs, such as hope or want, indicate that the action of the complement verb will be in the future (expressing future possibilities). Such verbs are usually followed by the to-infinitive:

Lindsay hopes to fly to London next week.

Examples include: agree, ask, allow, aspire, attempt, cause, choose, consent, dare, decide, decline, encourage* expect, hope, instruct, intend, offer, mean, need, permit, persuade, plan, prepare, promise, propose, swear, remember, tell, threaten, try, want, warn, wish* Some verbs (e.g. those marked with an asterisk above) can be followed by object + infinitive:

John expects Lindsay to fly to London next week.

A small number of verbs are followed by an object + bare infinitive, e.g. have, help, let, make: Have Mr Smiley come in, please.

Verb + gerund

When a gerund follows a verb, or verb + object, the meaning is normally that the situations described are already in existence, i.e. they are not future situations:

Lindsay hated flying.

However, a small number of verbs followed by a gerund complement point to the future. These include consider, contemplate, fancy, feel like, put off, suggest.

Lindsay is considering flying to London next week.

References

1 Sinclair, J (1990.255), Collins Cobuild English Grammar, London: HarperCollins 2 Quirk, R et al, (1985.213), A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, Harlow: Longman. 3 Thomson, A J and Martinet, AV (1980.184),b A Practical English Grammar, 4th edn, Oxford: OUP 4 Alexander, L G, (1988.178), Longman English Grammar, Harlow: Longman 5 Wood, F T, (1954.219), The Groundwork of English Grammar, London: Macmillan 6 Leech, G (2004.68), Meaning and the English Verb, 3rd edn, Harlow: Pearson

The Give That Keeps On Gifting: The Protean Nature of English Words, and Why That’s A Good Thing

English is constantly adding, modifying, and repurposing words.

Look, there’s one right now: repurpose. According to The American Heritage Dictionary, it is officially a word:

Etymonline cites its usage from 1995, so it is relatively new. It is made by adding re- to the word purpose, which can be either a noun or a verb. My money is on noun, because the new construct comes out of business or technical jargon and purpose as a verb is pretty seldom heard. Not that it would be wrong. In fact, it would not be surprising if purpose used as a verb were revived as a back-formation of repurpose.

In this season of giving, let’s look at the words give and gift. Give is a verb and gift is a noun, right? True. But haven’t you ever found some mechanical thing to be loose when it was supposed to be tight and said, “I feel a little give in it”? Of course you have. Verb has been nouned. You nouned it yourself.

Similarly, we’ve all heard someone use the word gift as a verb: “She gifted them all with front-row seats to the concert.” And whether our inner fussbudget winces or not when we hear it said that way, it is still a legitimate usage. Face it: the traditional verb form give doesn’t say as much, and simply isn’t as precise. “She gave them all front-row seats to the concert.” That doesn’t exactly carry the connotation of presenting them with a gift, does it? She could have been paying them back for prior favors, or because she lost a bet — any number of non-giftish reasons come to mind.

Who can forget the “regifting” episode of the immensely popular TV show Seinfeld? (Hmm, that occurred right around the time repurpose came into the lexicon. Coincidence?) And if we admit that the writers and actors on that show were all very gifted, we’ve now adjectived a noun. We might even have adjectived the noun very giftedly, in which case we’ve adverbed the adjective. It goes on.

There really is nothing to be afraid of. Languages change, and words get overloaded, adapted, modified. Some people abhor this condition. Some feel language should be as precise as mathematics: see John Quijada’s artificially constructed language, Ithkuil, if you don’t believe me. Me, I prefer the richness of everyday speech, and the creative way people adapt words to mean new things. Isn’t it more colorful and descriptive to say a basketball player bricked a shot, rather than falling back on the boring and pedestrian missed? A horrible shot in basketball looks like someone throwing a brick, not a ball, and if we verb the noun we get a shot that has been bricked.

Language is a living thing. Let’s never forget that. If words stop changing, a language starts dying, just as our bodies do if our cells stop dying and being reborn.

While we’re on the subject, let’s look at that verb: live. The noun form is, of course, life. Since the 1830s, the noun lifer has referred to a prisoner serving a life sentence. But wait a sec, didn’t it have to become a verb first? Isn’t a verb at least implied there: lifer, one who lifes? No? Let’s move forward in time and notice a shift in meaning: lifer now includes someone who is serving “for life” in the military. I recently read the book Generation Kill by Evan Wright, who was embedded with a platoon of Recon Marines that participated in the assault on Baghdad in 2003. After Saddam’s army was defeated, one of the Marines, Corporal Ray Person, is quoted as he grouses about the battalion first sergeant’s return to his meddlesome “lifer” ways. Person complains:

Ahh, there it is. Crude though his statement may be, his verbing of a noun that arose from the prior verbing of the same noun is pure poetry. And exactly right for the sentiment the soldier wished to express. What is a lifer sergeant doing to Marines when he makes their lives miserable with a lot of petty regulations? He is lifing them. And he is doing so in the imaginary-yet-somehow-very-real language Cpl. Person vulgarly calls retardese, which consists, presumably, of one stupid, ungrammatical statement after another spoken in a near-incomprehensible hillbilly drawl.

I hope you can’t find any give in my arguments. But I wish to gift you with one final thought on the protean nature of English. Wallace Stevens said it about poetry, but it goes for language in general as well:

It has to be living, to learn the speech of the place.

It has to face the men of the time and to meet

The women of the time. It has to think about war

And it has to find what will suffice. It has

To construct a new stage.

In other words, it has to be a living, changing entity, continually adapting, being adapted, constructing a new stage. Fortunately for all of us, it is.

That vs Which: A Pragmatic Approach

“There’s glory for you!”

H. Dumpty, founder of linguistic pragmatics

If you’re looking for a balanced discussion of the That vs Who/whom/whose/which controversy, go here. I’m not interested.

A hundred years ago the Fowlers put forward a modest proposal. Linguistic bureaucrats elevated this proposal to a Rule, linguistic libertarians resisted; and today the Fowlers’ proposal is an Issue hotly contested by Conservative and Liberal ideologues.

I have no taste for political disputation. While my sympathies lie with the Liberals (who in the Fowlers’ day would have been the Reactionaries), my experience is that I am never profoundly disturbed by the actual usage of the Conservatives (who a hundred years ago were the Radicals). And neither side is going to budge from its position, each is deaf to the other’s arguments and writes or redacts according to its own judgment; so I see little point in rehashing the arguments.

I’d like instead to adopt a non-partisan and non-ideological approach, and come at the T/W question from a different angle. I’m a writer, my concern is to make the most effective use I can of the tools which come to my hand. The Fowlers themselves grounded their proposal in the economic argument that “if we are to be at the expense of maintaining two different relatives, we may as well give each of them definite work to do (The King’s English, 1908).” I may hope, then, that others will find some value in exploring the pragmatic and non-doctrinal considerations which govern my usage in my writing.

“Writing”, I say; but the spoken language is both historically and methodologically prior to the written, and most of us aspire to something of the spontaneity and freshness presumed to reside in oral usage; so it may be useful to see what ordinary speech tells us.

I happen to possess a modest corpus of semiformal speech—videotapes of impromptu interviews with a dozen college-educated U.S. speakers from various regions and callings. Scanning the transcripts for uses of relative pronouns (and consulting the tapes where there was any ambiguity) yielded three interesting findings:

- Ordinary U.S. speech does not distinguish lexically between restrictive and non-restrictive clauses. Indeed, the paratactic construction imposed by improvisation makes the distinction itself difficult to maintain. How do you categorize a clause which is clearly, to the ear, an afterthought, but which could make sense as a restrictive clause? —Here’s an example; the speaker is discussing a table of numbers (a dash represents a pause):

The difference between 154?—(points) that is actually available?—and and the 149—(points) which the budgeting exercise produced?— is another opportunity for life insurance . . .

- All the W forms are very rare: that is absolutely predominant by at least fifty to one. If the W forms disappeared from the spoken language they would never be missed.

- Again and again I heard that after a clause followed by a pause (and sometimes repetitions of that)—and then the speaker settled on what he was going to say—which might be a relative clause (restrictive or not), an adverbial clause, or a clause to which that was entirely irrelevant.

So—should the written language follow Liberal logic, and abandon the W forms altogether?

Of course not. No craftsman forsakes the use of a tool simply because amateurs do not use it. Finding 3. above is instructive: speakers prefer that because it’s the all-purpose tool, adequate in all circumstances. But the writer has an entire workbench of specialized tools, and leisure to choose between them.

Should we then unite behind the Conservatives, and use T and W to distinguish restrictive and non-restrictive clauses?

Again, I think not. The usage is not distinctive either for the ordinary reader or for many of the ideologues. And it is redundant: all of us distinguish these clause-types by means of the comma. The T/W distinction is unnecessary here.

Let’s instead use the W forms where they’re most useful: in any relative clause. The W distinctions, between who, whom, whose and which, allow us to signal reference and syntax more clearly and more smoothly. When it can be done gracefully, omit the relative pronoun altogether; but let’s use that as a relative pronoun only under pressure of what the Fowlers call “considerations of euphony”.

This not only exploits the W distinctions more fully, it makes that more effective and efficient, too. that is horribly overworked: it takes 17 columns in the OED to discriminate its uses. No word except to is more likely to appear multiple times in a sentence with different meanings. As Dumpty noted, that comes at a cost: no word is more likely to confuse the reader’s eye and mind.

I have for thirty-five years avoided the use of that as a relative pronoun. I use W forms almost exclusively, in all contexts: marketing copy, stage plays, voiceovers, business proposals, legal drafts, training videos, my doctoral dissertation.

And you know what?—I’ve never been called out for it. Not by clients—not by actors—not by academics.

I commend this approach to your consideration.

“Impenetrability! That’s what I say!”

H.Dumpty

Adspeak

I have a confession to make: I’m really a prescriptivist at heart. I have an idea in my head of how the English language ought to be used, and deviations from that ideal bother me. They especially bother me when I have to listen to them on a daily basis, courtesy of television commercials.

For example, one of my first questions on ELU was about the laundry detergent commercial tagline of “Style is an option. Clean is not.” As I noted, while it’s obvious what they meant, it’s also not quite what they said — if clean is out of the question, then why would anyone ever use this detergent? It would be such a simple fix, too: just replace “an option” with “optional”, and you’d have an unambiguous and grammatically correct tagline.

Another recent violator is the luxury car commercial that ends with (for example) “More power, more style, more technology, less doors”. (The list of more adjectives changes with different versions of the advertisement.) Every time that ad plays, I swear I can hear the collective moan of pain from English teachers and grammar nerds across the country. Again, the fix would be simple: fewer would contrast with more just as well as less does, with the added advantage of not hurting the ears of potential customers.

But oddly enough, other misuses of language don’t bother me. For example, the economy car ad tagline “unbig, uncar” elicits a grin, not a groan. I was wondering why this is, and I think I’ve hit on something: “unbig, uncar” doesn’t have an easy correction that would get the same idea across using more conventional grammar. “Small, not a car” just doesn’t have the same impact. So it’s obvious that this slogan is deliberately ungrammatical.

It turns out that even for a prescriptivist, a mistake made on purpose isn’t a mistake at all. (Warning: black hole, ahem, sorry, tv tropes link.)

Articles: “A” vs. “An”

One of the prevalent questions on the English Language and Usage – Stack Exchange is about whether a or an is the correct indefinite article to use. It’s a straightforward question, but like all questions, there are subtleties that raise further questions.

General Rule

The question of “a” vs “an” is always decided by the pronunciation of the word that follows the article, without exception. Words that begin with a vowel sound, such as apple, egg, or owl, use the indefinite article an.

I ate an apple yesterday.

All other words, i.e. words that begin with a consonant sound, such as cake, pie, or book use the indefinite article a.

I read a book yesterday.

Vowels, Consonants, and their Sounds

Some words are a little trickier though, and if you’re not familiar with common English pronunciation, you may want to take note of things that can trip people up. Note that I said vowel sounds and consonant sounds earlier, not just vowels and consonants. There’s a reason for this—many people think that vowels and consonants are letters, and making it clear that this is misleading is vital. We’ll keep up this distinction to reinforce the concept.

In fact, vowels and consonants are sounds. Letters thought of vowels (i.e. a, e, i, o, u, and sometimes y) can have a consonant sound, and vice versa, so it just might be a good idea to check a dictionary with pronunciations when you’re unsure. We’ll be using IPA pronunciations here, but any good dictionary will have some reasonable pronunciation guide.

Aitches

If you have a word that begins with the letter h, there’s a good chance that the h is silent (i.e. doesn’t make a sound). For example, take the word hour, which has a pronunciation of /aʊ̯ɚ/, and compare it with the word hospital, which has a pronunciation of /hɒspɪtəl/. Note that hour, even though it begins with a consonant, does not begin with a consonant sound as the initial h is silent; rather, it begins with the subsequent vowel sound. However, hospital does not have a silent h, and thus the h is pronounced as a consonant, and hospital is used with the article a.

I was at a hospital for an hour.

Wyes

There’s another common problem. Elementary school teachers seem to love teaching their students that there are five vowels (i.e. a, e, i, o, u), and sometimes y is a vowel as well. This is true because y can have both a vowel sound and a consonant sound, but it’s extremely misleading because these same teachers also instill the idea that the letters are in and of themselves the vowels.

But that’s going off on a tangent—when does y make a vowel sound? Just like with h, the answer is when it does. There are few guidelines to work with, but in most cases, when a word begins with a y and is not a proper noun (in which case you wouldn’t be using an indefinite article anyway), it’s probably a consonant sound. Still, you might want to check your dictionary if you’re unsure.

I had lunch on a yacht. /jɒt/

More Vowels and Consonants?

Another corner case I want to point out are words beginning with u. In a fair number of these, such as uniform, user, and unicorn, the u is actually making a consonant sound that’s much like the y consonant sound—it’s represented in IPA as /j/.

A unicorn became my very best friend.

Even though I’ve warned you about these pitfalls, there are more cases where vowels and consonants don’t seem to be what they should be, so if you don’t know how to pronounce a word, a dictionary can be your very best friend (unless you have a dog, in which case the dictionary will be your second best friend).

Acronyms and Initialisms

Ok, so we’ve gotten the basics down. But English isn’t that straightforward—what happens when we bump into acronyms and initialisms? Remember, the general rule is 100% right—we’re only calling it general because we want to look at the corner cases. In fact, this is one of the few rules in English that is never violated in Standard English.

How you pronounce the acronym/initialism directs the article you choose. If you say FAQ as three different letters, i.e. /ɛf.eɪ.kjuː/, you begin with a vowel sound and should use an. If you say FAQ in one syllable, i.e. /fæk/, you’re beginning with a consonant sound and should use a.

A NATO exercise will begin in thirty minutes.

An AIDS treatment is due to be tested shortly.

N.B. If you’re wondering why we don’t make the distinction between acronyms and initialisms here, it’s because there’s disagreement about the exact definition of the terms.

Parenthetical Statements

Another common area of confusion is parenthetical statements. Imagine that you’re reading the sentence. If you include the parenthetical statement when you read it aloud, the first word in the parentheses decides the article. If you skip it, then use the word immediately following the close of the parentheses. When in doubt, it’s usually safer to assume the parentheses would be read aloud.

If you’re wondering when a parenthetical statement might come after an article, it most often appears to insert an adjective (e.g. I need a/an (lovely) evening to myself).

But My Pronunciation Is Different

You might disagree with some of my examples because you pronounce the word following the article differently than I do, and that’s perfectly fine. I’ve done my best to choose cross-dialectal examples, but some dialects are so different it’s hard to make all examples work. What you should keep in mind is that you’re writing or speaking to an audience—if they’re all from a specific region, try to use the pronunciations they would when you’re choosing articles. If they’re from a variety of regions, then choose the most common pronunciation.

What are you on about now? (Prepositions: on vs about)

When something has a topic, is it ON that topic, or ABOUT that topic? This question on, or about, which preposition to use comes up fairly often. Martha’s answer tries to explain some of the connotations that may be present when using certain words.

- A discussion about a topic — this implies that the discussion was just a conversation, really, and it might not have stayed strictly on-topic.

- A discussion of a topic — this brings to mind a true discussion, going into all sorts of details of the topic (and only the topic).

- A discussion on a topic — here I picture the discussion to be somewhat one-sided, almost a lecture.

I’m afraid to say that I don’t agree with these explanations. My instinct is that “about” and “on” are pretty much equivalent in meaning, as FumbleFingers wrote.

But if there are two words, and they both serve a similar purpose, which should we choose? People must care about this, because they keep asking. It turns out that EL&U is not the only place people have asked. A blog post on twopens.com asked the Chicago Manual of Style editors which was better:

She gave a lecture on recycled plastics or about recycled plastics.

A lengthy discussion ensued until one editor pointed out that it didn’t matter at all, since the meaning was perfectly clear and concise.

Until, of course, you have a sentence like

I once attended a lecture on the surface of Mars. (How did you get there?)

Now we have a pickle. The word “on” has many definitions, so once your sentence invokes one of those other definitions you risk confusing your reader. If you’re careful, you can spot the double meanings and edit your sentence accordingly. Or, you can be cautious and just choose “about” which has less potential for error.

Finally, if you want to just go with the flow, you can simply do whatever everyone else is doing. If you can figure out what that is, of course.

Ratio of On to About

(Ratio of less than one means About is used more)

| Word | Ratio |

|---|---|

| News | 0.73 |

| Discussion | 0.6 |

| Lecture | 4.82 |

| Article | 2.73 |

| Book | 1.35* |

*Note: Many false positives here, such as: “found the book on Amazon.com”, “book on tape”, etc.

From my crude Corpus search, it seems that there is no clear winner in usage. The numbers for “on” are inflated by the fact that many examples are false positives, yet there still is an overwhelming usage of “on” for certain phrases. So don’t get too hung up about about, or go on and on about on. It’s all okay.

How to Ask out an Apple

Hello there Paul!

I understand you’re staying in England to learn the language.

That should be “I am here to learn English.”

I think you mean “Please explain to me.”

Well, you were explaining your reason for coming to the UK. In English, we explain our reasoning by saying I am [present continuous verb] to [verb].

For example:

- “I am reading to learn.”

- “I am running to catch up.”

We would not say “I am running for catching up”.

So, Paul, how has your week been?

Oh yes? And what is that?

Yes, “that” can be used in a similar way to “it” to refer back to a previous subject, such as your problem.

Well, I’m not the best person to ask for romantic advice, but I can certainly help you ask him out with good English. Tell me what you are going to say to this fruit.

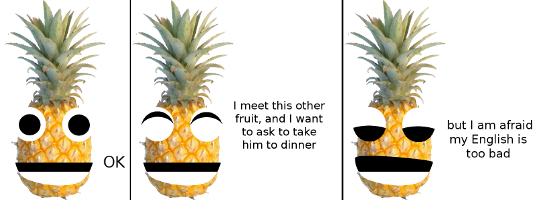

Good so far.

Hmmm, well, what you want to say is understandable, but there are a couple of grammatical errors and the second sentence would be phrased differently by a native speaker.

I’ll deal with the second sentence first. A native speaker would be more likely to say “Would you like to come to dinner with me?” This allows Angus to answer a question, rather than be faced with a statement of fact that needs no answer.

The first of the two errors I’ll deal with is where you said “for many times”. First, the word “for” doesn’t go with the phrase “many times”; “many times” just goes by itself.

- “I threw the ball many times.”

However, you are talking about two types of event (hanging out and talking) that occurred on more than one occasion. English has various words to cover this, for example: a lot, often, frequently.

So the difference can be characterised like so: When you play squash, you hit a ball against a wall many times. If you play squash each week, then you play it frequently.

The final thing I would change is the tense of your opening sentence. “We are hanging out and talking” means that that is what is currently going on, but “many times” means that this is something that has happened before. What you want to indicate is that hanging out and talking have happened in the past, and each time is complete, i.e. not still ongoing. For this, English has a tense called the present perfect.

Examples include:

- “I have been to the doctor.”

- “We have gone on holiday.”

- “They have eaten us out of house and home.”

To form the present perfect you take have and add the past tense of the verb. So in your sentence you want to say, “We have hung out and talked“.

So Paul, what are you going to say to Angus?

Excellent. To make it clear that you enjoy Angus’s company, you could add “, which I enjoyed very much.” to the end of the first sentence. So it would become “We have hung out and talked a lot, which I enjoyed very much.” This would emphasise how you feel about Angus, and hopefully persuade him to say yes!

No problem. Go get him!