Archive for September, 2012

Typography: Striking Language (part 1)

Typography is all around us, every minute of every day. I’m willing to bet that, this blog post notwithstanding, there are at least five different typefaces within reach of you at this moment. I’m hedging my bet, because it’s probably closer to ten or fifteen. You may think little or not at all of typography, but it is equally important to language as the spoken word. By definition, typography is the study, use, and design of identical repeated letterforms. Throughout history, these forms have taken shape and morphed from the shifting popularity and availability of writing implements and surfaces.

Language itself is rooted in visual communication. Before we had language, we communicated with imagery. The story of typography begins with man’s initial use of petroglyphs (rock engravings), pictographs (cave paintings), and pictograms to preserve business transactions, tell stories, give warning, and record history.

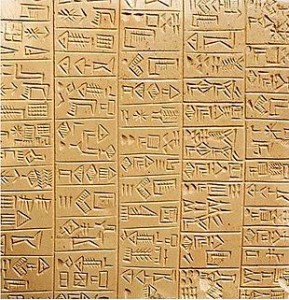

The ancestral awakenings of modern typography are found in cave drawings, tablets, and Egyptian hieroglyphics, ideography that served to support and preserve spoken tales of the joys and threats that comprised the daily existence of early man. From the oldest Sumerian cuneiform tablets (fig. 1) to the digital typefaces of today, written language has persevered as a crucial auxiliary to the spoken word. The written word is invaluable as a means of preserving the past and language itself. The beautifully-written word adds a nuance of artistic flair and reveals a concurrent history of its own.

The English alphabet evolved from the Latin one used by the Romans and is thought to have grown from Greek, Semitic, and Etruscan influences. Our modern letterforms developed around 100 BCE, and by 100 CE, two common forms of Roman scripts were in use. About one hundred years later, parchment and then paper were developed, and their portability was revolutionary to the spread of written language and of literacy in general. Over the next few hundred years, the Greeks were writing using reed and quill pens with nibs, the changing widths of which altered the pens’ strokes and resulting letterforms.

The earliest form of typographical mass production, relief printing, was developed in China around 700 CE. By 1300 CE it had reached the Europeans, who by 1440 CE were using the technology to print entire books comprised of woodblock-cut text and images. A German blacksmith, Johannes Gutenberg set the printing world on fire with his invention of a moveable type printing press which allowed individual letterforms and punctuation to be set and reused again and again. Gutenberg’s contribution defined the identical repetition that defines typography and largely satisfied the printing industry for the next 400 years. Printing technologies from then on have advanced to serve the growing literate population that Gutenberg’s invention had spawned.

As a discipline, typography is as complex as any other serious subject: the magic of readability and presentation is rooted in an often mathematically-calculated aesthetic. In selecting type, the main concern is the matter of readability. More than just legibility, readability is a marriage of legibility and good design. You’re likely reading this post in a typeface called Georgia, a very popular face designed for the ease of screen reading. Just as Gutenberg’s moveable type served to facilitate the changing times, digital type must capitulate to the limits of the medium to maintain the base principle of legibility. Bad type stands out and good type goes unnoticed, quietly serving and preserving ideas with beauty and aplomb.

Writing Good ‘Meaning’ Questions

On any Stack Exchange site, a question must be tagged. Here at EL&U, our most popular tag is the meaning tag, with over 2700 questions filed as such. Unfortunately, this tag is often misused, and many questions bearing this tag are closed, with some being subsequently deleted. Luckily, the EL&U blog is here to save the day.

Here is a set of criteria for good meaning questions:

Good meaning questions…

- are not General Reference

- are applicable to a wide audience, not just the OP (not Too Localized)

- ask about…

- words or phrases that do not make sense when interpreted literally

- words or phrases that are ambiguous

- potentially archaic words or phrases

- words or phrases that have different meanings in different dialects

- other things that are generally deeper than a simple definition

1. Not General Reference General Reference questions are questions that can be fully answered with a single link to a place that is specifically designed to provide the information in the question. These sources include online dictionaries or etymology sites.

To put it more simply, a General Reference question is too basic for EL&U. In my experience, General Reference is the most common reason for question closure. The meaning tag is more likely to be used on a General Reference question because the name and description of the tag are slightly deceptive, especially to those who don’t speak English well; it’s deceptive because meaning sounds a lot simpler than the questions should be.

Almost all definitions are easily found by using search engines or by checking dictionaries directly. In most circumstances, asking for a simple definition is too basic.

2. Not Too Localized Questions that get closed as Too Localized are unlikely to help anyone in the future, meaning that the question at hand simply does not apply to many people. These questions can stem from a user finding an unfamiliar word or phrase somewhere else on the Internet, a news article, etc. EL&U and the meaning tag seem like prime places to ask about the meanings of these unfamiliar words or phrases, but if that word/phrase has been made up and used among just a handful of people, then it likely has no established meaning, and thus cannot be explained.

More simply, they don’t mean anything to anyone other than the few who use it. Asking about the meanings of these types of phrases is not likely to be accepted, either with the meaning tag, or without.

3. So what can I ask about? Well, if your question isn’t ruled out by criterion #1 or #2, it stands a good chance of being acceptable. There are a few final things to be concerned about, but these apply to all questions—make sure it’s legible, sensible, and well-written. Be certain to clearly state the exact question you have at some point, and include research that you’ve done yourself. The list of good question criteria is a good place to start, and don’t hesitate to pop into chat to ask about your question if you’re not sure it’ll do well. Here are two examples of good meaning questions: Which day does “next Tuesday” refer to? What does “information porn” mean?

Thanks for reading, and good luck with all of your future meaning questions.