Posts Tagged ‘learning’

The Basics of Limerick Composition

It is difficult to judge someone’s language proficiency. There are plenty of standardised tests, but in my humble opinion, they just prove someone can pass a test, not how good they are at using a language.

Two things that can indicate a good grasp of a language, at least in the case of English, are the abilities to pun and to rhyme.

Punning is probably more difficult than rhyming, since it requires not only a good grasp of pronunciation and a swift vocabulary, but also knowledge of the meaning of a great many words and idioms.

One of my favourite British pastimes that involves a lot of rhyming and occasional punning, is that of writing limericks. I won’t be concentrating on puns, since they are not essential to limericks.

I can see you’re all wondering what this wondrous thing, a limerick, is. Limericks are a type of verse, invented as a parlour game. They follow a simple pattern:

- They have five lines.

- The last words of the first, second and fifth lines must have the same rhyme.

- The last words of the third and fourth lines must have the same rhyme.

- The first, second and fifth lines have the syllable stress pattern of duh DA duh duh DA duh duh daaa (approximately).

- The third and fourth lines have the syllable stress pattern of duh duh DA duh duh DA (approximately).

I say that they have five lines, but often limericks are written with the third and fourth lines combined into one. It is simpler to learn how to write limericks by thinking of them as having five lines. The stress patterns should be adhered to as well as possible, but can be fudged somewhat in order to include a rhyme. The only strict rule is the rhyming pattern of AABBA.

I think an example will be most illustrative. One of the great British poets, Edward Lear, was famous for his limericks. Here is an example:

There was an old man who said, ‘See!

I have found the most beautiful bee!’

When they said, ‘Does it buzz?’

he answered, ‘It does,

I never beheld such a bee!’

You can often tell an Edward Lear limerick by how two of the lines, usually the first and fifth or second and fifth, make the rhyme using the same word (in this instance, bee).

As an example of how being able to rhyme can demonstrate one’s proficiency in English, if you look at the third and fourth lines of Lear’s limerick, you can see that does rhymes with buzz. While the pronunciation of does is probably one of the earlier things learnt in English, it might not be obvious to all due to how the spellings differ.

Another point is the ability to know which words will best fit the stress patterns for the limerick. This is something that can only be learnt through extensive practice. In our above example, the words fit the stress patterns almost exactly. The fourth line, however, does rely on a pause at the end to keep the rhythm.

Some say that for a limerick to be a true limerick it must be salacious or rude in some way. I do not agree. I think that beyond the structure of the limerick, the main semantic rule is that they should be light hearted. A serious limerick is a pointless thing.

So if you’re wondering how well your ability in English is coming along, try composing a few limericks. The easier you are finding it, the better your grasp of English is.

How to Ask out an Apple

Hello there Paul!

I understand you’re staying in England to learn the language.

That should be “I am here to learn English.”

I think you mean “Please explain to me.”

Well, you were explaining your reason for coming to the UK. In English, we explain our reasoning by saying I am [present continuous verb] to [verb].

For example:

- “I am reading to learn.”

- “I am running to catch up.”

We would not say “I am running for catching up”.

So, Paul, how has your week been?

Oh yes? And what is that?

Yes, “that” can be used in a similar way to “it” to refer back to a previous subject, such as your problem.

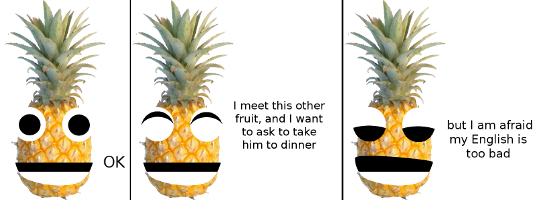

Well, I’m not the best person to ask for romantic advice, but I can certainly help you ask him out with good English. Tell me what you are going to say to this fruit.

Good so far.

Hmmm, well, what you want to say is understandable, but there are a couple of grammatical errors and the second sentence would be phrased differently by a native speaker.

I’ll deal with the second sentence first. A native speaker would be more likely to say “Would you like to come to dinner with me?” This allows Angus to answer a question, rather than be faced with a statement of fact that needs no answer.

The first of the two errors I’ll deal with is where you said “for many times”. First, the word “for” doesn’t go with the phrase “many times”; “many times” just goes by itself.

- “I threw the ball many times.”

However, you are talking about two types of event (hanging out and talking) that occurred on more than one occasion. English has various words to cover this, for example: a lot, often, frequently.

So the difference can be characterised like so: When you play squash, you hit a ball against a wall many times. If you play squash each week, then you play it frequently.

The final thing I would change is the tense of your opening sentence. “We are hanging out and talking” means that that is what is currently going on, but “many times” means that this is something that has happened before. What you want to indicate is that hanging out and talking have happened in the past, and each time is complete, i.e. not still ongoing. For this, English has a tense called the present perfect.

Examples include:

- “I have been to the doctor.”

- “We have gone on holiday.”

- “They have eaten us out of house and home.”

To form the present perfect you take have and add the past tense of the verb. So in your sentence you want to say, “We have hung out and talked“.

So Paul, what are you going to say to Angus?

Excellent. To make it clear that you enjoy Angus’s company, you could add “, which I enjoyed very much.” to the end of the first sentence. So it would become “We have hung out and talked a lot, which I enjoyed very much.” This would emphasise how you feel about Angus, and hopefully persuade him to say yes!

No problem. Go get him!